Operating Room as a Stage and Classroom: Intraoperative Learning in Anesthesiology

Robina Matyal, MD

Published July 3, 2025 | Clinics in Medical Education

Issue 7 | Volume 1 | June 2025

Goals of Ethics and Professionalism Curricula

Defining Practice and Execution in Clinical Anesthesia

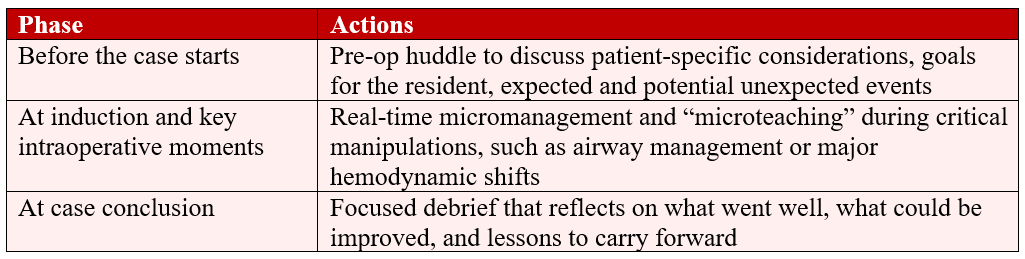

TABLE 1

Creating a Structured Learning Environment in the OR

- Use the case itself as the foundation for problem-based learning. Build discussions around physiological responses, pharmacologic decisions, and unexpected developments.

- Encourage residents to anticipate and plan responses to possible outcomes both typical and atypical.

- Reinforce decision-making frameworks rather than rote memorization, fostering flexible, adaptive thinking.

A Different Training Model

Unlike aviation, where trainees simulate for thousands of hours before touching a real aircraft, anesthesiology residents are learning on the job. While simulation and didactics are valuable, the OR remains the core site of skill acquisition and judgment formation.

Given this reality, we must maximize the learning potential of the OR:

- Normalize microrunning commentaries during surgery: short, focused guidance that keeps the resident engaged without overwhelming.

- Build a culture of immediate, respectful, and constructive feedback.

- Debrief with intent: not just what happened, but why, and how to do better next time.

FIGURE 1

An attending teaching medical students and residents in the operating room

The Contrast with the Aerospace Industry

In industries like space and aviation, training prioritizes exhaustive simulation and theoretical preparation, with pilots spending thousands of hours in simulators before ever operating a real aircraft, devoting roughly 90% of their time to practice and only a small portion to actual execution. This model minimizes risk and prepares individuals for rare, high-stakes events through meticulous rehearsal. In contrast, anesthesiology, embedded in the real-time clinical environment, reverses this approach: execution itself becomes the primary platform for learning, while practice is integrated through structured training sessions, mentorship, and ongoing education. Given the high stakes and relentless pace, anesthesiology demands a continuous cycle of learning, application, reflection, and adaptation.

Conclusion

In anesthesiology, the operating room is both the stage and the classroom. It is where residents perform, learn, and grow under the direct guidance of experienced faculty. Through structured feedback, problem-based teaching, and active participation, the intraoperative setting becomes the most authentic and powerful learning environment available.

To train safe, thoughtful, and adaptive anesthesiologists, we must invest in teaching during care, not after. That means embracing intraoperative teaching as a deliberate act, even in the face of production pressure. Only then can we ensure that our learners are prepared—not just to practice medicine, but to execute it with excellence.