Perioperative Stroke

Sumeeta Kapoor, MD, Yifan Bu, MD, Rae Allain, MD

Published July 3, 2024 | Clinics in Medical Education

Issue 7 | Volume 1 | June 2025

Perioperative stroke is defined as a new cerebrovascular event that occurs intraoperatively or within 30 days of surgery. These strokes may be either overt or covert. The incidence of perioperative stroke varies depending on the type of surgery: in carotid endarterectomy (CEA), it is approximately 1–1.4% in asymptomatic patients and 2.3–4.3% in symptomatic patients, with higher rates in those with a recent history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA). In non-cardiac, non-neurological surgeries, the incidence ranges from 0.1–0.7%. Perioperative strokes are associated with increased morbidity, mortality, and long-term neurocognitive decline.

Timing and Recommendations for Carotid Endarterectomy (CEA)

Current recommendations advise that CEA for symptomatic carotid stenosis should be performed as soon as the patient is neurologically stable, ideally within 14 days of symptom onset but not within the first 48 hours following a stroke. Multiple large cohort studies and meta-analyses have shown that performing CEA within 3–14 days after the index event offers the best balance of efficacy and safety. In contrast, very early CEA (within 48 hours) is associated with a higher perioperative risk, particularly in patients who have experienced a disabling stroke. For patients with mild symptoms such as a TIA or minor stroke, early intervention within 3–7 days is associated with improved neurological outcomes and long-term durability, though the risks increase if surgery is performed too soon. Contraindications to early CEA include disabling stroke (modified Rankin Scale ≥3), large infarcts involving more than 30% of the ipsilateral middle cerebral artery territory, altered consciousness, and neurologically unstable conditions such as fluctuating or worsening neurological deficits. Major strokes within the preceding 48 hours also warrant delayed intervention.

CEA After Intravenous Thrombolysis (IVT)

CEA following intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) for acute ischemic stroke or TIA should generally be delayed for at least 5–7 days. This delay is necessary to minimize the risk of intracranial hemorrhage and neck hematoma, as the risk of hemorrhagic complications is highest within the first 48 hours after IVT.

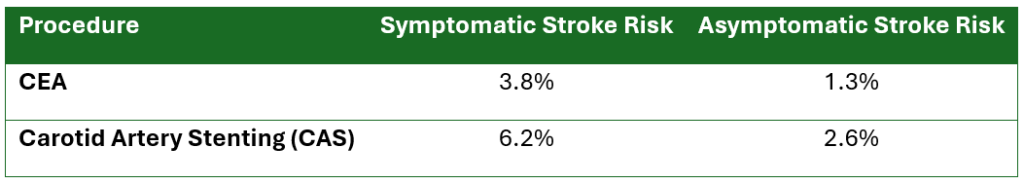

CEA vs Carotid Artery Stenting (CAS): Stroke Risk Comparison

Choice of Anesthesia

Both local or regional anesthesia (LA) and general anesthesia (GA) are acceptable for carotid surgery. Large randomized trials such as the GALA trial, as well as Cochrane reviews, have demonstrated no significant difference in the rates of perioperative stroke, death, or myocardial infarction between the two anesthetic approaches. While some registry and observational studies suggest that LA may be associated with lower rates of perioperative cardiac complications, these findings have not been consistently confirmed. Therefore, the choice of anesthesia should be individualized based on patient factors such as age and comorbidities, as well as the experience and expertise of the surgical and anesthesia teams.

Perioperative Medications

Aspirin, statins, and antihypertensive agents, including beta-blockers, should be continued throughout the perioperative period for carotid surgeries. Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) and anticoagulation require individualized assessment based on each patient’s specific risk factors and indications. For patients undergoing TCAR or transfemoral CAS (TFCAS), continuation of DAPT is generally recommended.

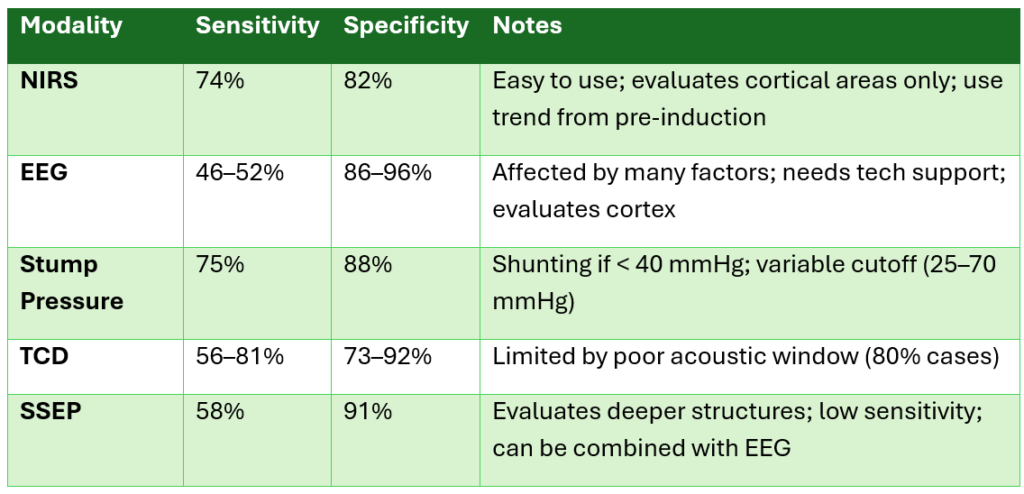

Intraoperative Monitoring (for Awake Patients)

Key Takeaway Points

Successful management of patients undergoing carotid surgery requires strong multidisciplinary team coordination, preoperative risk stratification, and optimization of comorbidities. Careful management of perioperative anticoagulation is critical, and elective surgical procedures should be delayed when feasible—typically for 3 to 6 months in patients undergoing non-cardiac, non-neurological surgery. Intraoperative hemodynamics should be closely monitored and maintained within 10% of preoperative levels. Maintaining effective, closed-loop communication with the surgical team and establishing clear postoperative hemodynamic goals are also essential for minimizing complications and ensuring optimal outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Shu L, Aziz YN, de Havenon A, et al. Perioperative Stroke: Mechanisms, Risk Stratification, and Management. Stroke. 2025 May 30. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.125.051673.

2. Lindberg AP, Flexman AM. Perioperative stroke after non-cardiac, non-neurological surgery. BJA Educ. 2021 Feb;21(2):59-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bjae.2020.09.003.

3. Cui CL, Dakour-Aridi H, Lu JJ, et al. In-Hospital Outcomes of Urgent, Early, or Late Revascularization for Symptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis. Stroke. 2022 Jan;53(1):100-107. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032410

4. Society for Vascular Surgery Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Extracranial Cerebrovascular Disease. AbuRahma AF, Avgerinos ED, Chang RW, et al.Journal of Vascular Surgery. 2022;75(1S):4S-22S. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2021.04.073.