Do’s and Don’ts of Intraoperative Teaching

Sara Neves, MD

Published October 1, 2024 | Clinics in Medical Education

Issue 3 | Volume 1 | September 2024

In academic medicine the new year begins in the summer. New interns, residents, fellows, and faculty necessitate efficient teaching strategies. Trainees need to learn quickly, but new faculty need to be able to teach. It is a helpful time to review proven methods of effective clinical teaching and avoid bad teaching habits that undermine learning.

Here, we will briefly review key features of adult learning theory, recognize differences about teaching in the clinical environment as compared to the classroom, review effective teaching strategies and learn to avoid common pitfalls in clinical teaching.

Adult learners are typically characterized by the fact that they are largely more volitional and self-directed, in addition to having fully matured brain capacity. Effective adult learners are self-directed, have a readiness to learn and an intrinsic learning motivation. If we think about adult learning settings, they are ones in which the learner has chosen their environment—chosen to attend university, or pursue a particular career path, or train in a specific job. In contrast, child learners lack mature decision-making capacity and are in school settings which are mandatory with a prescribed curriculum that the students do not choose, impacting their motivation and readiness to learn. Additionally, adult learning tends to be driven towards problem solving and utilization of acquired knowledge, whereas child learners have not yet acquired much knowledge, so learning is more curriculum driven.

Where do our trainees fit in? Residency is a time of transition. Medical schools typically introduce adult learning techniques with problem-based teaching, flipped classrooms, and group discussions, but these opportunities are limited and constrained by a need to get many learners to acquire a significant amount of knowledge in a short period of time. As they progress through residency, we see more of the adult learner motivation. If we compare and contrast the medical school experience and residency training, we see key differences that define the goals of that educational environment.

Medical school still remains primarily curriculum driven, with many assessments (tests, Shelf Exams) and despite the incorporation of some active and adult learning techniques still follows the passive pedagogical model of education. This fits with the overall goal being the acquisition of large amounts of knowledge in four short years. In contrast, residency training is much more problem-based, with the learning bouncing around in a non-linear way, varying from learner to learner based on exposure and experience. The resident may apply principles of hemodynamic management in different ways in a pediatric case versus a cardiac case versus a neurosurgery case, yet this very much fits the goals of an adult learning environment, which is the active process of applying acquired knowledge to solve problems. Additional acquisition of knowledge is driven by the need to solve a particular problem (ie take care of the patient in front of the trainee) rather than to build a fund of knowledge in and of itself.

However, there is still a period of transition. Learners may be students on June 30th and doctors on July 1st, but they are not entirely prepared for the new learning environment or the expectations of adult learning that the training environment brings. They arrive from the high stakes high pressure environment of school where for 20 years they are exposed to the same style of education—being taught a topic, study that topic, take a test on that topic. Combining work with learning is entirely new, and the relative dearth of formal assessment (tests) leaves learners feeling unmoored and uncertain of how to proceed. Because trainees are adults, we make the mistake of expecting them to be adult learners, despite being in a more traditional education environment for much longer than other professionals their age. Instead, we should design the residency learning environment to grow trainees into adult learners. This necessitates a different approach.

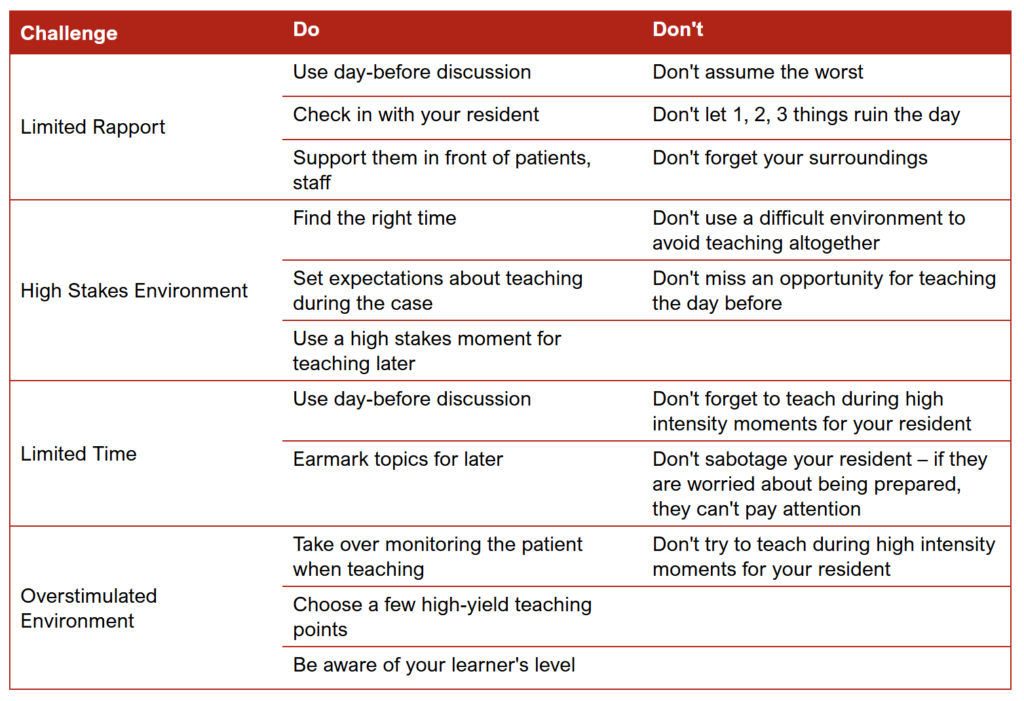

The clinical teaching environment, especially in anesthesiology can prove challenging to these learning goals. The perioperative space is high stakes, with considerable production pressure and limited teaching time, prioritizing efficiency, and can be overwhelming with data and tasks. In addition, the teacher-learner relationship—the strength of which is critical to effective education—can be difficult to build when faculty change day to day and have attention split between supervising trainees in multiple operating rooms.

REFERENCES

1. Long M, Blankenburg R, Butani L. Questioning as a teaching tool. Pediatrics. 2015 Mar;135(3):406-8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3285. Epub 2015 Feb 2. PMID: 25647682.

2. Neher JO, Gordon KC, Meyer B, Stevens N. A five-step “microskills” model of clinical teaching. J Am Board Fam Pract. 1992 Jul-Aug;5(4):419-24. PMID: 1496899.

3. Neville G. Chiavaroli & Jacob Pearce. (2024) Twelve tips for developing effective marking schemes for constructed-response examination questions. Medical Teacher 0:0, pages 1-7.