Curriculum Development in Medical Education - Part I - Laying the Foundation with Kern’s Framework

Federico Puerta Martinez, MD, Dario Winterton, MD

Published April 18, 2025 | Clinics in Medical Education

Issue 6 | Volume 1 | April 2025

The development of a robust and impactful curriculum is essential in Medical Education for shaping competent healthcare professionals. A systematic approach, such as Kern’s six-step model, offers a structured pathway for curriculum design. This article will focus on steps 3 and 4 of this framework. These two steps are crucial for translating identified needs into a tangible and effective educational experience.

Step 3: Defining Goals and Objectives

After a thorough needs assessment (steps 1 & 2), the next step is to articulate clear goals and objectives that will guide the curriculum. Goals are broad educational aims, while objectives are specific, measurable statements of what learners should achieve. Objectives guide the selection of educational content and methods and enable evaluation of learners and the curriculum.

Educational objectives can be categorized into three main types:

- Learner Objectives: These focus on what the learner will know, feel, or be able to do as a result of the curriculum. Learner objectives can be further divided into:

- Cognitive Objectives: These relate to knowledge and intellectual skills.

- Affective Objectives: These address attitudes, values, and beliefs. Psychomotor

- Objectives: Also known as skill or behavioral objectives, these focus on physical skills and actions.

- Process Objectives: These relate to how the curriculum will be implemented. For example, a process objective might be that each learner will complete an online module prior to a workshop.

- Outcome Objectives: These relate to the broader impact of the curriculum on healthcare, patient outcomes, and population health. An outcome objective could be that a higher percentage of graduates from the program will practice in underserved areas.

To create holistic objectives, there are some well-accepted frameworks. We will focus on three complimentary ones:

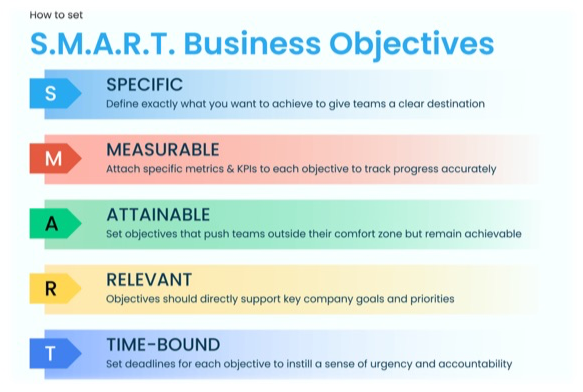

- SMART criteria ensures the objectives are correctly structured.

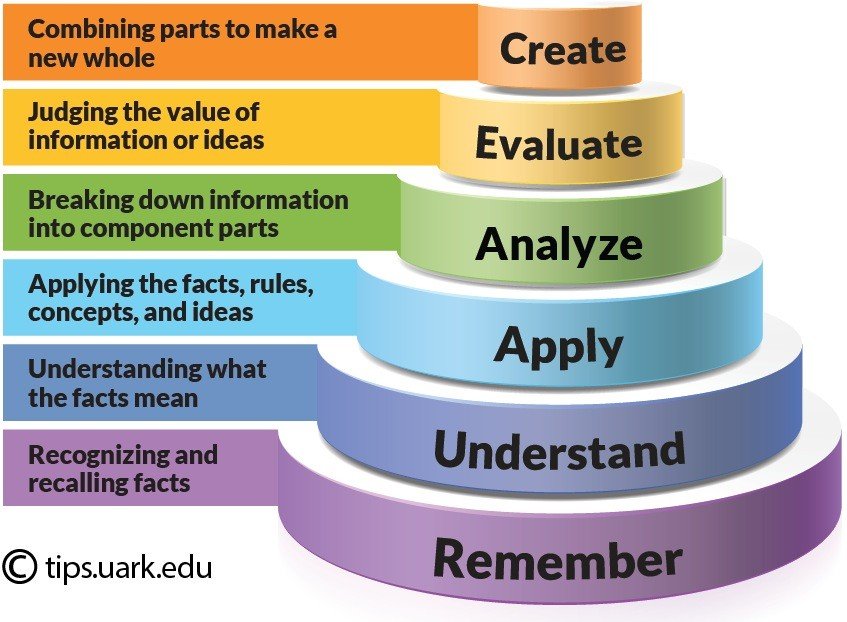

- Bloom’s Taxonomy ensures the objectives target appropriate levels of cognitive learning.

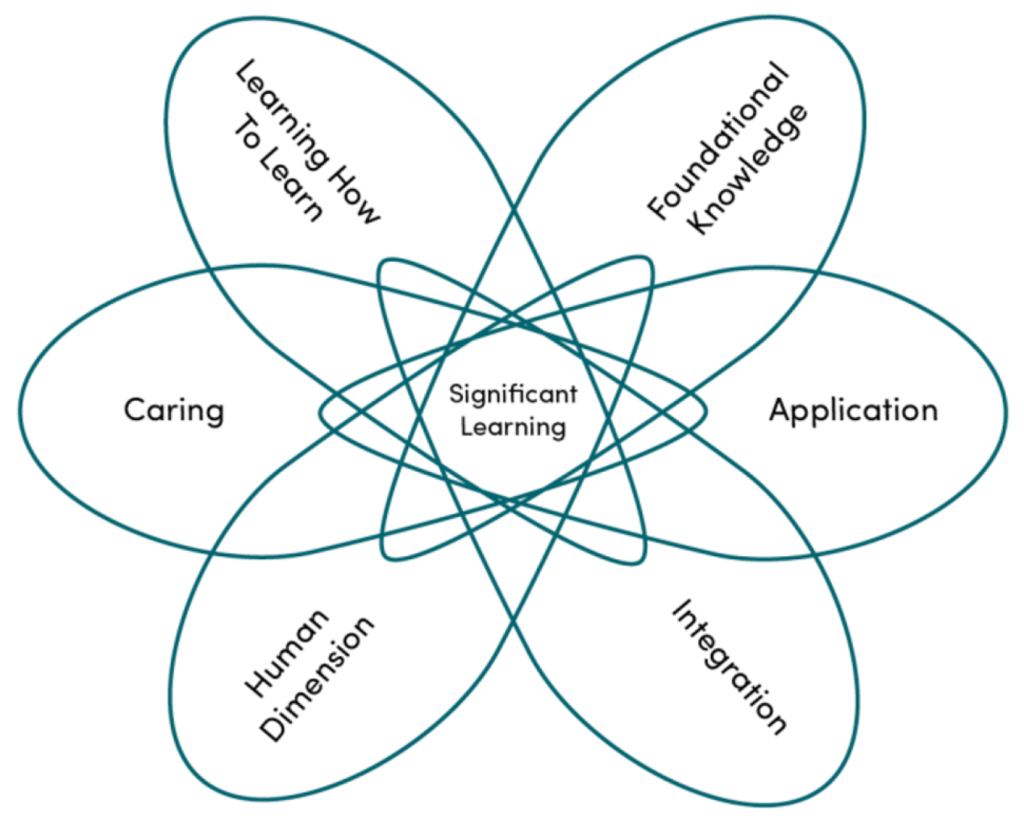

- Fink’s Taxonomy ensures that the objectives aim to create a meaningful, holistic, lasting impact.

By integrating these frameworks, educators can craft objectives that are specific, measurable, cognitively challenging, and significant, leading to more effective and engaging curricula.

A key characteristic of well-written objectives is that they are specific and measurable. A useful framework for creating objectives is to include five basic elements: Who, will do, how much/how well, of what, and by when. For instance, “By the end of the workshop, each student will describe six fundamental principles of patient safety” includes all five elements. It is also important to use clear and precise verbs that are not open to multiple interpretations. Verbs like “analyze”, “evaluate” and “create” are associated with higher-order cognitive skills, while verbs like “list” and “describe” refer to lower-order skills.

Step 4: Educational Strategies

Once clear objectives have been defined, the next crucial step is to choose appropriate educational strategies. This involves carefully considering both the content (what will be taught) and the methods (how it will be taught). Educational strategies are the means by which the curriculum’s objectives are achieved and are considered the heart of the curriculum. A variety of methods can be used to achieve educational objectives. These can be broadly categorized into methods for cognitive, affective and psychomotor/skill-based learning.

Strategies for Cognitive Objectives

- Lectures: Traditional lectures are useful for presenting information efficiently to a large audience. However, they can be enhanced by incorporating interactive elements and encouraging active learning.

- Self-paced Learning: This includes the use of online modules, videos, or readings that learners complete independently. Spaced repetition of content and interleaving concepts can improve retention.

- Concept Mapping: Learners create visual representations of how concepts interrelate to promote deeper understanding and critical thinking.

- Case-based Learning: Learners apply new knowledge and skills to real or virtual patient cases. This promotes active learning and integrates new and prior knowledge.

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL): Learners work in small groups to solve complex problems. PBL requires intensive faculty and case development.

- Team-Based Learning: Emphasizes collaborative learning and problem-solving within teams. This is useful for large groups.

- Virtual patients: These are interactive computer simulations of clinical scenarios that allow learners to develop their clinical reasoning skills.

Strategies for Affective Objectives

- Role Modeling: Faculty members serve as exemplars of professionalism and empathy.

- Reflection: This involves activities such as writing, and discussions that promote self-awareness and emotional processing.

- Narrative Medicine: Using storytelling to foster empathy and deeper connections with patients.

- Arts and Humanities: Engaging learners emotionally and intellectually through activities such as theater workshops or visual arts.

- Exposure/Immersion: Placing learners into authentic or new practice environments to affect their attitudes.

Strategies for Psychomotor Objectives

- Demonstration: Instructors show learners how to perform skills.

- Supervised Clinical Experience: Learners apply skills under the supervision of experienced clinicians.

- Role-Plays: Learners practice communication and interpersonal skills in simulated scenarios.

- Simulation: The use of artificial models or standardized patients to practice procedures.

In addition to these methods, it’s also important to consider the use of technology to enhance learning. Digital education, which can include online learning, blended learning, and the use of games and gamification, offers new ways to engage learners.

Practical Application and Conclusion

As anesthesiology educators, we can apply these principles to design curricula that address the unique needs of our learners. For example, a curriculum on patient safety might include cognitive objectives such as “describe the principles of sterile technique,” affective objectives such as “appreciate the importance of teamwork in the operating room,” and psychomotor objectives such as “demonstrate proper technique for intubation.” Educational strategies might include lectures, case-based discussions, simulation scenarios, and reflective writing assignments.

Ultimately, the development of an effective curriculum requires a thoughtful approach that considers the specific needs of the learners, the desired outcomes, and the most effective methods for achieving these goals. By focusing on well-defined objectives and carefully selected educational strategies, we can create curricula that produce competent, compassionate, and capable healthcare professionals. Remember that educational experiences encompass more than just a list of pre-conceived objectives, and the best learning often derives from needs identified and pursued by individual learners. It’s important to remain flexible, creative and open to new and emerging educational strategies.

In the next issue, we will be covering the final 2 steps (Steps 5 & 6) of Kern’s Curriculum Development Framework.