Anesthesia For Neonate with Encephalocele Repair

K. Theophilus James, CRNA, Bettina Tassone, DNP, CRNA, Huma Syed Hussain, MD

Published July 3, 2024 | Clinics in Medical Education

Issue 7 | Volume 1 | June 2025

Each month, the Boston Africa Anesthesia Collaborative (BAAC) hosts grand rounds to promote case-based learning and knowledge exchange in anesthesia practice across resource-limited settings in Liberia. The May session focused on best practices for managing neonates with encephalocele.

Encephalocele is a congenital neural tube defect characterized by incomplete closure of the cranial vault, leading to the herniation of brain tissue through a defect in the skull. It is typically classified based on its location into anterior and posterior types. The clinical presentation of encephalocele varies depending on the size and location of the defect. Symptoms may include headache, visual disturbances, muscle weakness, microcephaly (small head size at birth), ataxia, facial malformations, nasal obstruction, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the nose or ear Long-term complications associated with encephalocele can include developmental delays, cognitive impairment, vision problems, growth retardation, and seizures.

While encephalocele is primarily congenital, some cases arise secondary to trauma or tumors. Associated syndromes include Walker-Warburg syndrome, Knobloch syndrome, Roberts syndrome, and Amniotic band syndrome. Risk factors include a family history of neural tube defects and inadequate maternal folic acid intake before and during pregnancy. Prenatal ultrasound and/or MRI can identify encephalocele in utero. Postnatal imaging assists in surgical planning and assessment of associated brain anomalies. Surgical intervention involves repair of the skull defect and excision of herniated brain tissue to prevent infection and further neurological compromise.

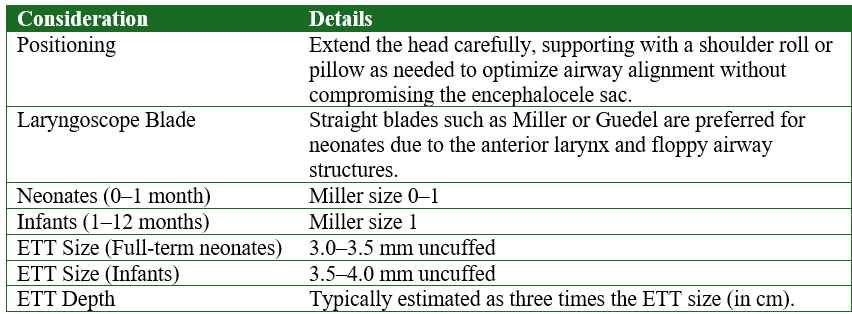

Anesthetic Considerations for Tracheal Intubation in Neonates with Encephalocele

Uncuffed vs. Cuffed Endotracheal Tubes

Traditionally, uncuffed endotracheal tubes (ETTs) were recommended for children under the age of eight, based on the belief that they exerted less pressure on the cricoid cartilage and thus lowered the risk of post-extubation edema. However, recent evidence has demonstrated no significant difference in post-extubation complications between cuffed and uncuffed tubes. In fact, cuffed ETTs offer several advantages: they often require fewer laryngoscopies and intubation attempts to achieve the correct size, reduce subglottic pressure, and minimize operating room anesthetic pollution and associated costs. Additionally, cuffed tubes help decrease the risk of aspiration, allow for more precise control of carbon dioxide levels (PCO₂), enable the delivery of higher airway pressures in cases of restrictive lung disease, and permit controlled cuff pressure without increasing the likelihood of post-extubation stridor.

Optimal Air Leak Assessment

After endotracheal tube (ETT) placement, the adjustable pressure-limiting (APL) valve should be set to 25 cmH₂O to apply an inflation pressure of 20–25 cmH₂O. Auscultation should be performed to detect an audible air leak at the glottic level. If no leak is heard at this pressure, it suggests that the ETT may be too large and should be replaced with one that is 0.5 mm smaller in diameter.

The presence of an air leak at 20–25 cmH₂O closely approximates tracheal capillary pressure and is important for preventing mucosal ischemic injury.

Case Report

A 20-day-old female neonate weighing 3.5 kg presented for surgery. Preoperative laboratory evaluation revealed a hemoglobin level of 16 g/dL. Anesthesia was induced with 7 mg of ketamine. Tracheal intubation required two attempts: the first, using a Miller size 0 blade and a 3.5 mm uncuffed endotracheal tube (ETT), was unsuccessful due to absent chest rise and an audible air leak. The second attempt, with a Miller size 1 blade and a 4.0 mm uncuffed ETT, was successful, providing effective ventilation. Anesthesia was maintained with 0.5–1 MAC of isoflurane, 1.75 mg of atracurium, and 70 mg of paracetamol. Intravenous fluids included 10% dextrose and 0.9% normal saline. The patient was positioned in the left lateral decubitus position for the procedure, with an estimated blood loss of 30 ml. At the conclusion of surgery, neuromuscular blockade was reversed with 0.2 mg of neostigmine and 70 mcg of atropine. Postoperatively, the patient remained stable and was monitored in the post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) for one hour before being transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

Figure 1

Bulge at the base of skull

REFERENCES

1. Newth, Christopher J l et al. “The use of cuffed versus uncuffed endotracheal tubes in pediatric intensive care.” The Journal of pediatrics vol. 144,3 (2004): 333-7. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.12.018

2. Levitan (2013) Practical Airway Management Course, Baltimore